July 2, 2021

The US Currently Occupies a Position of Extraordinary Asymmetrical Leverage, But Its Unilateral Approach Entails Broader Geopolitical Risk Friday, 2nd July 2021. The first in a series As the world’s leading superpower, the US may have unmatched military strength, but in recent decades the US has preferred to weaponize economic sanctions as its instrument of choice to project power and influence around the globe. Economic boycotts, blockades and other trade sanctions have a long history dating back millennia. Sanctions became a more prominent tool of economic statecraft in the second half of the 20th century as the US and other Western countries saw financial and trade pressures as preferable to warfare as a means to enforce the new post-war global order, allowing countries in a position of economic power to achieve many of the same geopolitical ends without having to put boots on the ground and troops in harm’s way. Sanctions may be imposed on a multilateral or unilateral basis, but the US is the single indispensable player in the global sanctions game, with the most expansive sanctions coverage and the most aggressive and effective enforcement capability. Without the US, multilateral sanctions have no real teeth, and acting alone the US can still effectively impose its will on companies and individuals around the world to compel them to play by its rules. The power of US sanctions arises from the confluence of US dominance in terms of undisputed military, economic and technological leadership in a world which is globally-interconnected to an unprecedented degree. The centrality of the US role in the international order, and more particularly the dominance... June 25, 2021

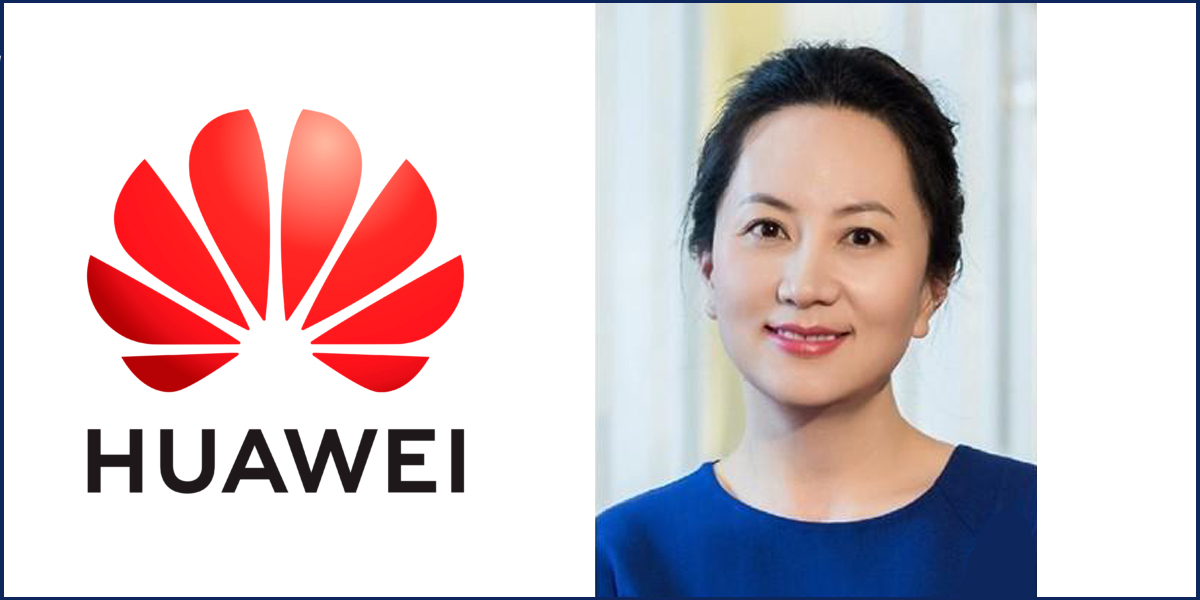

Ms Wanzhou Meng, the CFO of China’s telecom giant Huawei, has been fighting in Canadian courts against her extradition to the US since the end of 2018. Her legal team presented a fourth set of legal arguments in late March and early April to the Canadian Supreme Court. The lawyers sought to argue that the US cannot prosecute Ms Meng in this case as the US courts have no jurisdiction in the circumstances. US prosecution, they say, would violate the requirement of customary intentional law on jurisdiction in criminal cases. The final decision in the extradition case was recently delayed when the Canadian court allowed Ms Meng’s lawyers to review new documents after HSBC and Huawei settled in Hong Kong. The final decision should be handed down this summer. Ms Meng was arrested in December 2018 at Vancouver International Airport where she was transiting on her way to Mexico. The arrest was in response to the US extradition request: Ms Meng faces charges of bank fraud for misleading HSBC about Huawei’s business dealings in Iran – an act which would have put the bank in breach of the US sanctions against Iran. Ms Meng has been held under house arrest in Canada since then, maintaining her innocence and fighting for her release. Ms Meng’s lawyers have previously argued that the fraud allegations are unsubstantiated and false, and that Ms Meng is a victim of abuse of due process. The lawyers argued that there were irregularities in Ms Meng’s arrest and they sought to show that the restrictions on Huawei and Ms Meng’s arrest need to be understood in their... June 22, 2021

As data grows in value and importance, the phrase “data is the new gold” is now heard regularly in the corporate world. With 5G mobile networks and the internet of things (IoT), more data than ever is being mined and Singapore is in the prime regional position to store this new “gold.” In its 2019 and 2020 reports3, the consultancy Cushman & Wakefield ranked Singapore’s data center capabilities as sixth worldwide and first in Asia-Pacific market, which is “forecast to reach US$28 billion by 2024, 20% higher than the US$23.4 billion North American market.” The reports reasoned that data center players will “favor Singapore for its relative security to store mission critical data and the business-as-usual data in the neighboring countries.” Cybersecurity Laws In A Nutshell Singapore has adopted a framework of key legislation and sector-specific regulations to address cybersecurity issues. The Cybersecurity Act 2018 moved Singapore away from sector-based regulation and required cybersecurity service providers to gain a license. It empowered the Commissioner of Cybersecurity, amongst others, to establish mandatory codes of practice and reporting/auditing requirements for owners of critical information infrastructure (CII). A non-owner of CII has an obligation to cooperate in cybersecurity investigations by the commissioner. The Act is linked to the Computer Misuse Act which criminalizes cybersecurity offences such as unauthorized access to computers. The Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (PDPA) also requires organizations to implement security measures to prevent unauthorized access, collection, use or disclosure of personal data. At the same time, sector-specific regulations continue in force. For example, the Monetary Authority of Singapore publishes notices and guidelines on cybersecurity best-practice for the banking... May 12, 2021

By Alexander H. E. Morawa, S.J.D. On 9 January, 2021, the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) of the People’s Republic of China published its Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures.[1] The Rules are fairly detailed and comprise various substantive and procedural provisions. And yet, they remain vague and – perhaps intentionally – imprecise in crucial respects.[2] This article addresses these rules and considers the context of combating long-arm jurisdiction and countermeasures more broadly. The rules encapsule primarily two core aspects of “blocking legislation,” namely the prevention of the enforcement of foreign judgments and the compliance with orders of foreign authorities.[3] The ministry seeks to counteract only such legislation or measures that meet three criteria: a) they are unjustified; b) they are created by foreign (governmental or relevantly similar) entities, and c) they are applied extraterritorially. The “justification” criterion leaves much room for legal interpretation as well as political tactics on a case-by-case basis. For instance, regulating or even criminalising conduct damaging to national security or other fundamental state interests applying protective jurisdiction – as in the extradition case of Huawai’s Meng – are manifestations of the recognised (albeit extraordinary) permissive principle under international law and require heightened justification. “Foreign” and “extraterritorial” are more objective assessments to be made: given that the rules’ purport is to further compliance with international law and best practices in international relations (Art. 2), Chinese agencies will want to apply them consistent with standards established on the international plane. “Foreign” is a term that denotes another sovereign state, but not an international organisation or entity created by a treaty. Such... March 17, 2021

In December 2018, while transiting through Canada on her way to Mexico, Ms Wanzhou Meng was taken off her plane, questioned and arrested. Her arrest followed earlier restrictions imposed by the US government on Chinese telecom giant Huawei (of which Ms Meng is the CFO). What actually happened? Is it a campaign against Huawei or China? And if so, is the campaign, and Ms Meng’s arrest legitimate? The restrictions on Huawei and arrest of Ms Meng have taken place in a particular political context, in a struggle between China and the US for political and commercial dominance. One aspect of this struggle is technological dominance. In recent years, China repeatedly identified technological development and advancements as one of its strategies for the future. China’s key opponent and competitor is the US. Traditionally, the US had the upper hand thanks to its technological giants such as Apple and Google and the Silicon Valley hub. However, more recently, a number of Chinese national champions started challenging the US control of the global market. Huawei is probably the most significant example. Although it is privately owned, Huawei is nevertheless perceived as one of China’s national treasures. As such, it is inevitable that the Chinese government does exercise a degree of influence over its activities and – many say – its data. Citing Huawei’s close connection with the Chinese government, the Communist Party and Chinese Liberation Army, as well as the fear that Huawei’s technology and access to information could be used to spy on the US government, companies and individuals, the Obama administration (following a report from the House Intelligence Committee in... February 5, 2021

By James Min II[1] What do the December 1, 2018, arrest of Ms. Meng Wanzhou in Canada on behalf of the United States, the U.S. Presidential Executive Order (E.O.) 13943 of August 6, 2020, banning WeChat, E.O. 13942 of August 6, 2020, banning Tiktok, and most recently E.O. 13971 of January 5, 2020, banning Alipay, QQ Wallet among others, all have in common? Aside from the geopolitical friction or economic rivalry between China and the United States in recent years, the fact is that they all raise complex legal issues. Moreover, they highlight the importance of Chinese multinational companies’ need to engage in global business in even a more sophisticated manner when it comes to the conflict of laws and the extraterritoriality of U.S. export control and sanctions laws, while at the same time, on the U.S. side, it also calls for the need for the U.S. Government to address its concerns with Chinese technological rivalry in a more sophisticated and nuanced manner rather than addressing it with blunt instruments. As Chinese companies conduct business around the world and become even more technologically advanced, the trend appears to be that they will continue to be targets of many national policies. Thus, it will be even more important that in-house compliance and legal professionals at Chinese companies or those advising such companies help infuse best practices in not only compliance but in business strategies. Given the size and reach of the U.S. economy, technologies, and its legal system, it will be difficult for Chinese multinational companies to simply ignore or avoid the United States entirely in the near term.... Upcoming Events

Recent Past Events