HONG KONG TAX BULLETIN

HONG KONG TAX BULLETIN

A brief discussion on how MNCs should respond to the OECD’s new measures relating to Automatic Exchange of Information and Transfer Pricing issues

By Anna Chan, Partner and Josh Kwok, Associate, Oldham, Li & Nie

AEOI and the CRS – Enhanced tax controls on tax evasion

Anna Chan

We are living in a globalised world, and cross-border activities have become the norm in the last few decades. In the past, multinational corporations (MNCs) often adopt aggressive tax strategies by booking most profits in tax heavens where information sharing with foreign tax authorities is often minimal. The result is that tax authorities across the world often face difficulties in gathering sufficient offshore asset and transactional information of the tax payers to conduct tax assessments in their home jurisdiction. To unplug loopholes, the OECD has led the international effort in the implementation of Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) and adoption of the Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

In order for participating countries to enjoy the mutual benefits of information exchange, financial institutions (FIs) of a participating country are required to report financial information regularly to local tax authorities which is then transmitted to their overseas counterparts in exchange of similar information from other participating jurisdictions. It is noteworthy that more than 100 jurisdictions are already committed to AEOI implementation as at June 2020.

Why is this relevant to me?

Josh Kwok

Let’s assume that you are a tax resident of your home Country A and have offshore assets or income in Country B. If both countries are committed to AEOI, Country B will become duty-bound to share your financial information automatically with the tax authorities of Country A, such that the latter may track your offshore investments beyond national borders, carry out a tax avoidance investigation and enforce any non-compliance. The most typical types of information covered include tax return and financial statements, company directors/shareholders, company registration, interests, dividends, account balance or value, sales proceeds from financial assets, etc. Such new disclosure regimes have made tax evasion through non-disclosure extremely difficult, if not practically impossible, because offshore undeclared financial assets can now be targeted by a taxpayers’ country of residence.

In Hong Kong, legislative amendments were introduced into the Inland Revenue Ordinance in 2016 to enhance tax transparency and combat cross-border tax evasion. Information exchange is permitted where a bilateral agreement is concluded between the Hong Kong government and a partner jurisdiction. By the start of 2020, the number of reporting jurisdictions in Hong Kong has increased extensively to 126. FIs in Hong Kong are required by law to collect information of identified individual/corporate account holders and their financial account information for onward exchange with other jurisdictions. Furthermore, FIs in Hong Kong must require account holders to complete a self-certification form to declare their tax residence status, and any intentional or reckless false statement on residence status will constitute a criminal offence.

The AEOI regime is relatively new, which might explain why reports about defects in the CRS are not uncommon. For example, there are still many offshore jurisdictions without a public company register and the ultimate beneficial owners might remain unidentifiable. However, with increasing perfection over the CRS, the past practice of utilising offshore entities for secrecy or confidentiality purposes is deemed to be phasing out gradually.

Take-home message

Given the global enhanced tax transparency, in-house legal professionals should plan ahead with their tax advisers before implementing any cross-border transactions, especially where certain offshore financial information may be exposed and reported back to the tax authorities of the home jurisdiction. Quite often, they are no longer protected on the grounds of secrecy or client confidentiality. In addition, since the AEOI regime may take retrospective effect in some jurisdiction, companies with foreign operations are also expected to review past transactions to ensure that tax disclosure has been adequately made to avoid penalties imposed upon future investigations.

Transfer Pricing – how does it work?

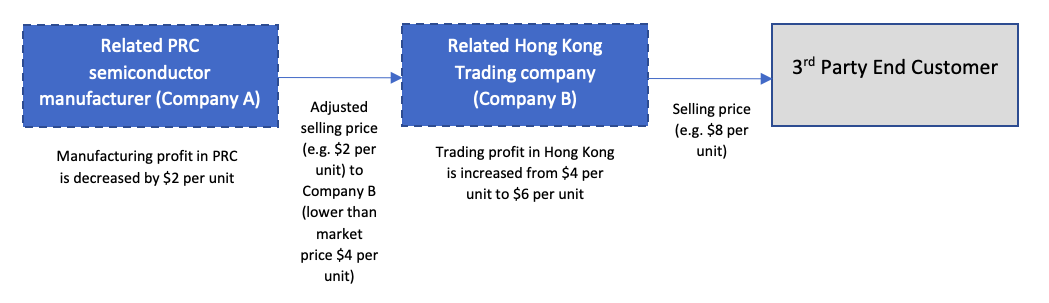

As mentioned above, tax authorities often pay close attention to MNCs to ensure that their modus operandi is not structured in a way that diverts domestic profits to overseas entities. A typical tax strategy which is often subject to challenge and scrutiny is called ‘transfer pricing’ – a practice adopted by MNCs to determine pricing, often artificially, between related entities and reduce tax liability for the group as a whole. This is most common where one entity is located in high-tax rate regime and another overseas company is in a low-tax rate jurisdiction. Imagine Company A is a PRC semiconductor manufacturer and Company B is a trading company in Hong Kong set up to facilitate onward global sales. The group may manipulate intercompany pricing by suppressing product price of Company A such that part of the manufacturing profits could be shifted from the PRC to Hong Kong when they are sold to third-party end customers. The group’s profits are thus subject to a more favourable tax rate in Hong Kong. This example can be illustrated in the following diagram.

Against this background, tax authorities around the world have taken active steps to prevent artificial pricing manipulation through anti-avoidance legislation to combat erosion of their tax revenue. Although details in the legislation may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the common objective is to enforce an ‘arm’s length transaction’ rule that requires pricing to be based on similar transactions done between unrelated parties. We shall briefly discuss below relevant Transfer Pricing law and practice and latest update in Hong Kong.

Transfer Pricing (TP) in Hong Kong

Prior to the legislative amendment in 2018, s.20 of the Inland Revenue Ordinance (IRO) (now repealed) had long been the general provision used to deal with TP issues. Under this section, if a non-Hong Kong resident carried on business with a resident with whom he was closely connected and the operations were arranged in such a way that they resulted in the Hong Kong resident producing no Hong Kong profits or less than ordinary profits, the non-Hong Kong resident’s business would be deemed as carrying on a business in Hong Kong, and thus chargeable to Hong Kong tax. Currently, TP issues in Hong Kong are mainly curbed by s.50AAF (alongside with other anti-avoidance provisions) by empowering the Hong Kong Inland Revenue Department (HKIRD) to impose TP adjustments on income or expenses in accordance with the arm’s length principle if a transaction has been made between two associated persons which (i) differs from the one which would have been made between two independent persons and (ii) confers a potential Hong Kong tax benefits. This principle corresponds to the OECD TP Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Administrators (issued in July 2017) (Guidelines) and became effective from 1 April 2018 (i.e. the 2018/19 Year of Assessment). It is worth noting that the burden in proving an arm’s length transaction falls upon the taxpayer and should they fail to satisfy the HKIRD, it may make adjustment accordingly.

Mandatory Documentation – a ‘3-tiered’ approach

Master File and Local File

Despite the introduction of the new legislation, we understand that some enterprises in Hong Kong are not aware that they could be subject to the three levels of TP reporting requirements. In fact, with effect from April 2018, any Hong Kong entities engaging in related party’s transactions (RPTs) are required by the HKIRD to prepare a Master File and a Local File. They are required to disclose whether they are required to prepare any TP documentation when filing their Tax Returns. Nevertheless, an entity may be exempted from documentation requirements if at least two of the following exemption criteria are satisfied for a given accounting period:

- Total revenue of the MNC group does not exceed $400 million;

- Total value of assets does not exceed $300 million; and/or

- Average number of employees does not exceed 100.

In addition, Hong Kong entities are not required to prepare the Local File if the relevant RPTs do not exceed the following amounts:

- Transfers of properties (whether movable or immovable but excluding financial assets and intangibles) – HK$220 million;

- Transactions in respect of financial assets – HK$110 million;

- Transfers of intangibles – HK$110 million; and

- Other transactions – HK$44 million.

The HKIRD has issued Departmental Interpretation and Practice Notes No.58 setting out the detailed contents required in the Master File and Local Files. For instance, the Master File must contain a high-level overview of the company group (including global business operations and TP policies) in order for the HKIRD to evaluate any significant TP risks. As for the Local File, detailed transactional TP information specific to the enterprise in each jurisdiction, including details of transactions, amounts involved and TP benchmarking analysis with respect to those transactions must be documented.

Country-by-Country Report (“CbC Report”)

MNC groups are also required to file a CbC Report where the consolidated group revenue for the preceding accounting period is at least HK$6.8 billion and the group has constituent entities or operations in two or more jurisdictions. Such report should include (among other data) aggregate tax jurisdiction-wide information relating to the global income allocation, taxes paid, and certain indicators of the location of economic activity among tax jurisdictions in which the MNE Group operates.

Guidelines on TP Benchmarking Analysis

The Guidelines have set out five TP methods to establish whether an RPT is consistent with the arm’s length principle when preparing a benchmarking study. Identification of a suitable method for TP analysis is a very technical exercise and is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important for in-house lawyers to note that depending on the industry or business activities which taxpayers engage in, tax advisers often make use of external databases to conduct searches of financial data and to identify domestic data comparable to the RPTs and if such comparables are unavailable, then comparables from similar markets in Asia or other parts of the world will be used. In many cases, statistical concepts, such as the interquartile range, may be helpful tools in determining whether an RPT is consistent with the arm’s length principle.

Penalties

The HKIRD recognises the imprecise nature of TP and therefore caps the potential penalties at a level lower than for other tax offences. The penalty for non-compliance with the Rule is limited to 100 percent (as opposed to three times) of the tax undercharged. No additional tax will be imposed when the taxpayer has exercised a reasonable effort to determine the arm’s length amount. The HKIRD also takes the view that preparation of a Local File with a comparability analysis would be considered a reasonable effort in this regard, although more stringent penalties are imposed for omission or understatement of income.

Take-home message

It is not difficult for the HKIRD to identify entities who might have obligations to do TP documentation. Quite often, enterprises do not apprehend the immediate impacts of the new legislation on them simply because the HKIRD has not raised requisitions with the taxpayers yet. Many MNCs could therefore potentially be charged with non-compliance unless they fall within the statutory exemptions. It is therefore advisable to make preparations sooner rather than later because the evidential value is higher if a comparability analysis supporting TP calculation is done before (instead of after) an RPT is carried out. Given the technicality involved, it is always important to obtain proper advice from accounting and legal experts to reduce exposure to potential TP risks.

If you would like to discuss any points raised above in more detail, please do contact Anna and Josh on the details below.

E: anna.chan@oln-law.com

E: josh.kwok@oln-law.com