A Look at the psychological benefits of arbitration and the status of arbitration in Thailand

There are often many reasons cited as to why international arbitration should be the preferred method of dispute resolution for parties: it can be quicker, cheaper, the process is private, the award is final, and the parties have more autonomy over the process. Whilst some of these factors are debatable (especially in highly complex commercial cases), the fact that parties to an arbitration can have more autonomy than in traditional court litigation is usually less controversial. Party autonomy in arbitration is often a significant factor that persuades contractual parties to consider arbitration over other methods of dispute resolution. This is not surprising, as the need to have control and certainty is an innate human desire that often brings us security and peace.

Our need for control and certainty

There is no doubt that Covid has had a detrimental effect on the economy and many businesses. Most people would also agree that it has taken a significant toll on people’s mental health. Social distancing forced people to keep a distance and lose close contact with friends and colleagues. For some people, it meant a loss of social contact and socialising all together, due to fear of catching the virus if they stepped out of the safety of their homes. Lockdowns and school closures meant that more families were stuck at home, glued to their computers for work or online school and having to navigate the lack of privacy and personal space in their own homes. For working parents, the stress of juggling work from home, not knowing if their job is secure, and supervising their children as they studied online led many to extreme stress and more arguments both with their spouses and their children. Separation and divorce between couples were not uncommon. The unpredictability of when the pandemic would come to an end left many feeling helpless and hopeless.

It is not surprising then that psychologists were recommending people to manage their stress by knowing the facts but not obsessing over the news and doing what they could to prevent the spread of the virus. This is strongly connected to the idea that as humans, we feel a sense of confidence and security when we are able to control certain factors in our lives – for example, controlling our finances by keeping a budget or saving money, can make us feel secure. The converse is also true; when we focus on things that we cannot control, we lose that sense of security, and it often leads us into anxiety.

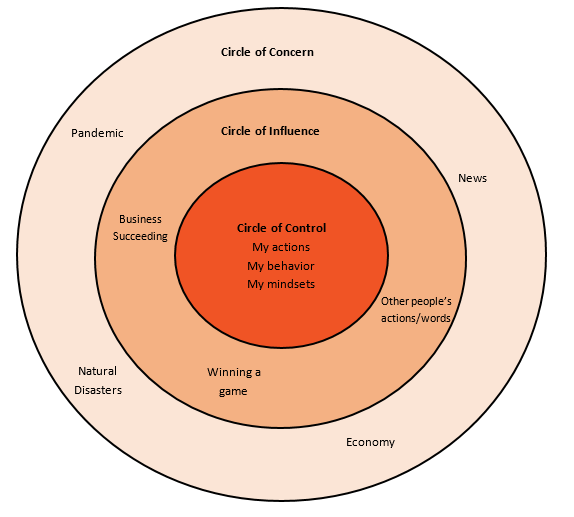

When supporting people with anxiety, counsellors will often refer to the concept of the “circle of control”. There are 3 circles to consider: the Circle of Control, the Circle of Influence and the Circle of Concern. This first circle consists of things you can control, such as your thoughts, words, actions and behaviour, mindset and decisions. The second circle is your Circle of Influence which includes factors you can influence, such as other people’s feelings or actions and certain outcomes of your actions (e.g., whether you win a sports game or whether your business succeeds). Unlike your Circle of Control, the factors in your Circle of Influence are not directly controllable by you but are affected or influenced by what you control. Finally, there is the Circle of Concern. In this circle, there are factors in our lives that we cannot really control, such as the natural disasters, pandemics, news and the economy. The following diagram illustrates the different circles just described:

The power of recognising the Circle of Control can be illustrated by how people responded to Covid. There were so many uncontrollable factors: the uncertainty of when the pandemic would end, travel restrictions, lockdowns, the timing of when we could be reunited with family or friends abroad and the impact of the pandemic on our future. These factors were in the Circle of Concern. However, by focusing on the inner Circle of Control and taking control of our actions such as sanitising our hands, wearing our masks, arranging remote working and meeting with friends online, many of us were able to manage the myriad of uncertainties and stress levels and adapt to the “new normal”.

Arbitration gives us a sense of control

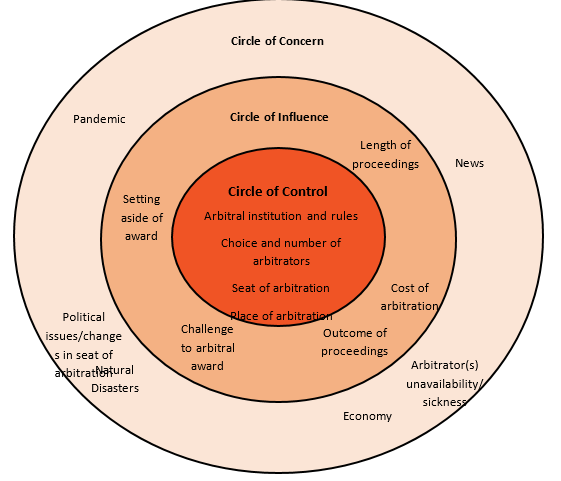

We can also apply this concept of Circle of Control to choosing our dispute resolution mechanism. The fact is that there are many uncertainties related to disputes including the length of the dispute, how much it will cost and what the outcome will be. This can create a lot of stress to the parties involved and it is not surprising that many simply avoid disputes for this very reason. This is where the element of party autonomy comes in to help relieve some of that stress.

Party autonomy is very prevalent in arbitration proceedings, even before the dispute commences. In a contractual clause, the parties can agree to resolve any disputes by arbitration and decide how many arbitrators should be appointed, where the arbitration should take place and which arbitral institution should administer the arbitration. The parties are therefore able to exert a level of control over a future dispute which can give them a sense of security in the event a dispute arises.

The ability to control certain matters in a dispute is psychologically significant. It provides the much-needed confidence and security that the parties need in entering into a contract but also, when a dispute arises they know (to a certain extent) what to expect. A well drafted arbitration clause will enable the parties to refer the matter to arbitration smoothly and usually appoint an arbitrator of their choice to determine their case, a process that is not available in traditional court litigation.

Flexibility in the arbitration process also means that party autonomy is prevalent throughout the course of arbitration proceedings. For example, most arbitral institutional rules provide a mechanism to allow parties to opt for expedited proceedings depending on the amount in dispute and certain other conditions. Many arbitral institutions are constantly seeking to improve their facilities and processes in order to make arbitrations more efficient and meeting the needs of the parties involved. In the last few years, virtual hearings have become readily available in arbitration to cater for Covid restrictions whilst virtual court hearings are still uncommon in many jurisdictions (including Thailand).

virtual hearings have become readily available in arbitration to cater for Covid restrictions whilst virtual court hearings are still uncommon in many jurisdictions (including Thailand).

The following diagram illustrates how arbitration can affect our circle of control, influence and concern:

Current status of arbitration in Thailand

Notwithstanding the positive attributes of arbitration proceedings, arbitration is still not a common method of dispute resolution in Thailand. There are many reasons for this, but one reason is that there still appears to be a lack of awareness about what arbitration means or entails for commercial entities in Thailand. As explained above, people crave certainty and stability in times of turmoil or conflict; hence, they often tend to default to the traditional dispute resolution mechanism they are familiar with when they encounter a dispute i.e. the Thai Courts.

That said, positive steps are being taken in Thailand to promote arbitration.

Firstly, there have been developments in the past several years which have made it easier for foreign arbitrators and representatives to work in Thailand. The amendments to the Arbitration Act in Thailand in 2019[1] enables a foreign arbitrator or representative who has been appointed in arbitrations in Thailand to request a “Certificate” from government agencies or organisations in Thailand (such as the Thai Arbitration Institute (“TAI”) or Thailand Arbitration Center (“THAC”)). The Certificate allows a foreign arbitrator or representative to obtain a work permit in Thailand and reside in Thailand for a specific period to work on a specific case. Another positive development is the extension of “Smart Visas” to highly skilled professionals in Alternative Dispute Resolution, including arbitrators and arbitration practitioners. A Smart Visa has additional privileges compared to a general visa including an exemption to obtain a work permit and the ability for the Smart Visa’s spouse and children to stay and work in Thailand (with certain conditions).[2] These are welcome changes in increasing party autonomy for those wishing to appoint foreign arbitrators or representatives in their arbitrations.

Secondly, the Thai courts have started to show a more pro-arbitration stance, by upholding arbitral awards and dismissing spurious challenges to the enforcement of arbitral awards. In Thailand, a ground that is often utilised by the losing party to set aside an arbitral award or object to the enforcement of the arbitral award, is that the enforcement of the arbitral award would be contrary to public policy. However, there have been a number of Supreme Court decisions which have upheld arbitral awards on the bases that intervening with the award would be contrary to the objectives to resolve the dispute by arbitration,[3] the arbitral tribunal had discretion to consider the facts of the case,[4] and the court could not repeatedly review the arbitral tribunal’s discretion on the admissibility and weight of evidence. [5] The most high-profile case which demonstrated a major movement in terms of pro-arbitration in Thailand is the case between Hopewell Holdings Limited and the Thai Ministry of Transport and the State Railway of Thailand, in which the Supreme Administrative Court reinstated the arbitral award in favour of Hopewell, despite the other parties being a State or State-related entities.[6]

Thirdly, there has been a lot of effort in recent years by the arbitration bodies in Thailand, including the TAI, THAC and Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb), in organising activities, seminars/webinars and training to raise awareness and education of arbitration in Thailand.

The future of arbitration in Thailand

The power and impact of arbitration cannot be understated. In addition to arbitrations enabling parties to have more control over their dispute, another significant advantage – particularly in Thailand – is that foreign arbitral awards are recognised and enforced more readily and easily than foreign court judgments. There are currently no legislations in Thailand that recognise foreign judgments, nor is Thailand a party to any bilateral or reciprocal enforcement agreements with other countries that enable ease of enforcement of foreign judgments. Therefore, if a party obtains a judgment in a foreign court, that party will need to commence fresh proceedings again in Thailand and only be able to use the foreign judgment as part of its evidence in those Thai proceedings. In contrast, any foreign arbitral award made in a country that is a contracting state to the Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958) (otherwise known as the New York Convention) can be enforced by the Thai courts under the Arbitration Act B.E. 2545 (2002). A party seeking to enforce an arbitral award can file an application with the Thai courts within three years from the date the award is enforceable. Although such application may be challenged by the opposing party, the legal grounds for the Thai courts to refuse enforcement are limited pursuant to the Arbitration Act[7] and we have been seeing some pro-arbitration judgments in the Thai courts, as stated above.

The benefits of arbitration go beyond the parties and can also have a significant impact on the economy. Foreign direct investment (“FDI”) is an important part of Thailand’s economic growth and many foreign investors would prefer arbitration over litigation in the Thai courts. International arbitrations that take place in Thailand can attract foreign arbitrators, lawyers and parties to come to Thailand, hence boosting tourism. Jurisdictions such as Singapore and Hong Kong have successfully incorporated arbitration into their ADR mechanism and the number of arbitration cases that go through the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) and Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) far exceed the number of cases that go through the Thai arbitral institutions.

In order for arbitration to be given more prominence in Thailand, several hindrances need to be addressed. First, there needs to be more training of what arbitration is and isn’t amongst law schools, corporations, and practitioners to raise awareness of the potential benefits of including arbitration agreements into contracts. Second, Thailand would benefit from having more experience with international arbitration, especially in light of the increasing FDI into Thailand and recent governmental policies designed to attract more foreigners into Thailand. One way this could be achieved is by welcoming more foreign arbitrators and representatives to be involved in arbitration cases in Thailand. The easing of immigration restrictions in 2019 as mentioned earlier has been a positive step forward in this regard. Third, in order to improve efficiency and enforcement of arbitral awards in Thailand, cases concerning enforcement or setting aside of arbitral awards should be assigned to, and determined by, judges who have substantive experience in arbitration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are many benefits in resolving disputes through arbitration and this article focused on one such benefit, namely party autonomy in arbitration and how this can have a positive impact on parties psychologically. Arbitration enables parties to have a sense of control over the dispute and exercise some of the factors in their Circle of Control. This leads to less anxiety and stress, which can be inevitable in a conflict situation.

In terms of arbitration in Thailand, it is hoped that positive trajectory we have seen in recent years including changes to the arbitration law and judicial attitudes will continue. As the economy picks up and FDI is expected to increase in the coming months, it is perhaps an opportune time to start considering arbitration as the preferred dispute resolution mechanism in Thailand.

For more information, please contact the authors or alternatively, our dispute resolution, litigation, and arbitration team members.

| Emi Rowse (Igusa), Partner and Head of Japan Practice | Emi has over 17 years of experience representing clients on complex commercial litigation and international arbitration proceedings under the ICC, LCIA, SIAC and TAI rules. Her expertise includes advising on commercial contracts, shareholder and joint venture disputes, employment, investigations (corruption, fraud and corporate governance) and competition law. Emi is also a professional counsellor, allowing her to comprehend the psychology of dispute resolution. Emi is half-Japanese and is fluent in Japanese. |

| Nattawut Cherdhirunkorn, Associate, Dispute Resolution, Litigation and Arbitration Practice | Nattawut is an associate active in dispute resolution, litigation, and arbitration practice. He possesses extensive experience advising foreign and Thai clients on commercial disputes, labour disputes, intellectual property disputes, class action disputes and arbitration. He has represented clients as the main litigator in Thai courts and arbitration centers. |

Emi Rowse (Igusa), Partner and Head of Japan Practice, Kudun & Partners

Emi has over 17 years of experience representing clients on complex commercial litigation and international arbitration proceedings under the ICC, LCIA, SIAC and TAI rules. Her expertise includes advising on commercial contracts, shareholder and joint venture disputes, employment, investigations (corruption, fraud and corporate governance) and competition law. Emi is also a professional counsellor, allowing her to comprehend the psychology of dispute resolution. Emi is half-Japanese and is fluent in Japanese.

Nattawut Cherdhirunkorn, Associate, Dispute Resolution, Litigation and Arbitration Practice, Kudun & Partners

Nattawut is an associate active in dispute resolution, litigation, and arbitration practice. He possesses extensive experience advising foreign and Thai clients on commercial disputes, labour disputes, intellectual property disputes, class action disputes and arbitration. He has represented clients as the main litigator in Thai courts and arbitration centers.

[1] Thai Arbitration Act (No.2) B.E. 2562 (2019)

[2] https://smart-visa.boi.go.th/smart/document/related/7_Announcement_of_the_Office_of_the_Board_of_Investment_No_Por_12_2561.pdf

[3] Supreme Court judgment No. 6411/2560 (2017)

[4] Supreme Court judgment No. 1465/2560 (2017)

[5] Supreme Court judgment No. 5560-5536/2562 (2019)

[6] Supreme Administrative Court Case No. 221-223/2562 (2019)

[7] Section 41, 42 and 43 of Thai Arbitration Act B.E. 2545 (2002)